As Irish skiers go, I’m pretty average, which is to say, I’m a bad skier. I can survival ski down most things, but the grace and elegance that the residents of my current home display on the slopes still eludes me. The benefits of learning to ski before developing risk awareness is all too apparent.

This was on mind when talking over the phone with Ben Pelto (University of Northern British Columbia). Those of you who have read other posts on this blog will know that Ben and I regularly work together during our summer fieldwork campaigns on the glaciers of BC (see On Conrad Glacier: Part 1 and Part 2). It was January, and we were discussing plans for a spring trip to the mountains, specifically Conrad Glacier, to observe how the winter had treated the glacier, and to scout out locations for the coming summer’s deployment of my weather stations. We were also planning to perform scans of the glacier using a ground penetrating radar (GPR), which would provide us with information on how thick the ice is, and the general shape of the underlying bed. This would all require some serious skiing.

Three months later, I am on a familiar road. With skis and camping gear in the back, I’m winding my way along the 750 odd kilometers from Vancouver to Golden, in eastern BC. Tonight, I’m meeting Ben and his sister, Jill, before an early morning helicopter flight to the ice.

After a brief delay to fix a clogged spark plug, we were in the skies above the Purcell Mountains, in good flying weather. It was my first time taking this journey in what were essentially winter conditions, and I was glued to the window as we maneuvered between the snow-covered peaks. We landed on the west flank of Conrad Glacier at 2,300m. Our campsite overlooked the jagged crevasses of the icefall that lay above our summer field sites. We dug out level platforms in the snow for our tents, and built up walls on the upper side to keep out the cold, downhill ‘katabatic’ winds that can develop on glaciers at night. In the front vestibules, we dug out lower platforms for storing gear, and putting on our boots in the mornings. Finally, we dug out a table and benches, and pitched a tarp over it to serve as our kitchen.

One of the main goals for this trip was to get an idea of how much snow the glacier had received over the winter, and how much water this snow will produce if it melts in the summer. To this end, we needed to take regular measurements across the glacier of the depth of this season’s snow, and its density. After setting camp on the first day, we skied down to the terminus of the glacier, and took a series of these measurements as we moved back up the slope. The weather was mild, and we were surprised to find a well developed melt water stream this early in the season, carving a channel into the surface snow. In the weeks preceding our trip, we had been keeping an eye on data from snow sensors located on mountains in this region. The early onset of spring was resulting in some significant snow melt, and the question on our minds was whether 2016 would prove to be as detrimental to the glaciers in this region as the record losses of 2015.

Late in the afternoon, with the weather beginning to turn, we pushed back to the shelter of our camp. After a warm meal, we watched the skies clear and felt the temperatures drop as the indigo twilight turned into a star filled mountain night.

Day two saw the beginning of our radar campaign. Our objective was to ascend to the upper plateau of Conrad, taking measurements along the way. The GPR system consists of a transmitter, and a receiver, each mounted on skis, with antenna extending out in between. The transmitter sends out a pulse of energy that passes down through the ice, and reflects off the bedrock underneath. The reflected energy is detected by the receiver, and the time taken by the pulse to travel to the bed and back tells us how thick the ice is. That’s the theory. The practical involves hauling this system over large swaths of the glacier, up steep slopes and icefalls, and around crevasses, trying to keep the system in line as much as possible. The relatively mild temperatures and strong sunshine made the hauling difficult, with the sleds prone to digging into the soft snow and tipping over. Despite this, we managed to cover significant ground with the radar, completing day trips of over 20km in some cases. Descending with the GPR was always an interesting experience, generally completed at the end of the day when we were returning to camp with already tired legs. We needed to act as brakes to stop the system from torpedoing down the mountain, requiring us to snowplow in our skis for kilometers downhill at a time, quad muscles screaming.

Our days on the glacier continued with combined snow depth/density measurements and GPR surveys. Working on the upper plateau of Conrad, the expanse of mountainous terrain around us was astounding. On every degree of the compass, snow covered peaks jostled for space on the horizon, like some jagged, storm blown ocean. A thought that keeps returning to me when working in these places, is what a privilege it is to be afforded such isolation and space in what is an increasingly crowded world. No traffic, sirens, voices, bleeping phones, or engines (apart from the occasional helicopter). To have access to the culture and community that living in a society provides is a great thing, but I am grateful for these opportunities to exist in solitude with nothing but survival and science to drive us on.

On one of our last days on the upper section of the glacier, we continued to record snow depth values to well over 3,000m elevation, and decided to push on to climb the summit of Mount Conrad; the peak which had loomed over us as we worked. We ascended on skies to within 50m or so of the 3,290 summit, before shedding our gear and scrambling the rock and snow of the final section. We climbed in beautiful weather (as had been the case for most of the trip; very unusual for Conrad), and our view from the summit was unimpeded in all directions. Turning from the summit, my thoughts were now fully occupied by the ski descent necessary to get off the mountain. The conversation I had had with Ben in January regarding my ski experience was echoing in my head as I clipped into my skis, and double checked my bindings. This was steep for me, but hesitating or leaning back would be the wrong option. I watched Ben and Jill drop in, took a solid breath, and followed.

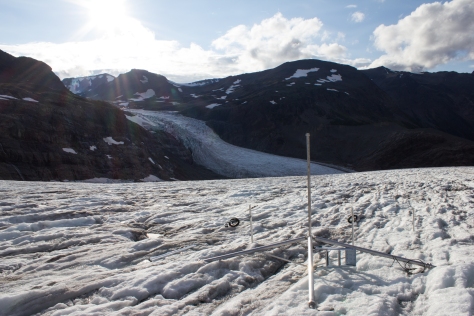

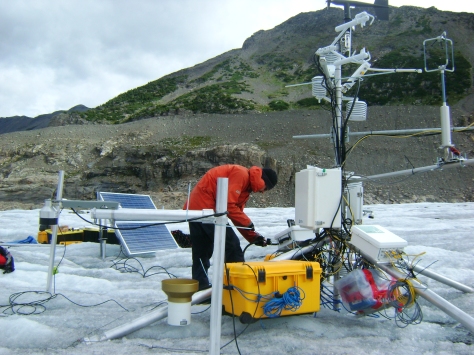

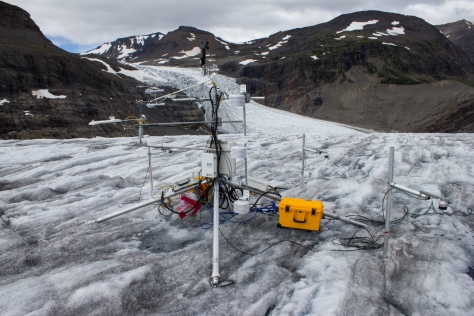

Our spring visit to Conrad had been very successful, with a wealth of snow and ice thickness data recorded over much of the glacier. Throughout our travels , I had been scouting for potential sites for installing the weather stations in the summer; just two short months away. One would be deployed in a similar location to last year; lower on the glacier in the ablation zone (the area on a glacier where more ice/snow is lost than gained from year to year). The other would be a more ambitious venture. The upper plateau at 3,000m would provide a unique and intriguing location to gain information on the glacier’s weather and melt relationships. It would also present a much harsher environment to operate in. Would we get a decent enough weather window to allow us to install the equipment (several days work), and if so, could the system withstand a season in tough and, as of yet, untested conditions? We would find out soon enough.