So a brief explanation as to why I’m here is required.

I’ve come to Vancouver to start a research project examining the relationships between the atmosphere and glaciers. I had been working as a research meteorologist for Met Éireann (Irish national weather service), when the opportunity arose to take up a PhD in Atmospheric Sciences at the University of British Columbia (UBC).

In a nutshell, my project aims to examine all the ways in which energy enters and exits the surface of a glacier, and how the balance between incoming and outgoing energy affects the melting or cooling of a glacier’s snow and ice. On a broader scale, my hope is to put this work towards improving our understanding of how glaciers will respond to changes in our climate. The initial plan is to install a weather station on a glacier in the Selkirk mountains in British Columbia, beginning this summer.

So, what’s required for the design?

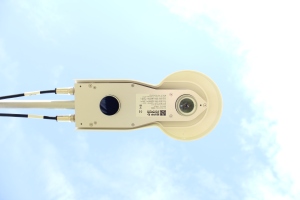

- The station needs to have sensors to measure each of the variables relevant to glacier energy balance. These include air temperature and humidity, radiation (for example, the incoming energy from sunlight), wind speed, and the transfer of heat and moisture by local air currents or ‘eddies’.

- It needs to be robust and reliable enough to operate in a remote mountain environment, unsupervised for several months.

- It needs to have its own independent power source.

The first step was to assemble and test all of the individual components in the lab, and to set up a method to automatically record and save the measurements made by each sensor. The lab is where you want to make your mistakes, and where you want things to go wrong. The more problems that present themselves in the warm, dry lab, the fewer that will come as a surprise when you’re struggling with cold fingers on the side of a mountain, or worse, when you’re already hundreds of kilometers away, oblivious to the fact that your PhD is falling into a metaphorical or very literal crevasse.

With things up and running in the lab, thoughts turned to how all the components will be brought together and mounted on the glacier, and on how to reliably power the station in such a remote setting. The plan is to rig the sensors on to a wide, stable tripod, with power provided from two marine batteries (like rugged car batteries for boats). The batteries will be recharged using a solar panel mounted nearby.

A test rig has been put together, and is now running at an outdoor site on campus. The main issues I’ll be keeping an eye on during this test include insuring the system records all the data it’s supposed to, when it’s supposed to, that the data makes sense and the sensors aren’t interfering with each other, and that a few cloudy days don’t cause my power system to flat line. Below are some images of the sensors I’m using and what they are for. For anyone interested, I intend to go into a little more detail on the science behind the project in future posts. I’m no expert though, so it should all be fairly readable!

All going to plan, we will travel to the glacier and install the weather station this July. There will be some modifications and additions leading up to this, including a new custom made 4 legged ‘tripod’ (quadpod?), and a timelapse camera system which I will be building in the meantime. Many more hours in the lab and office will be required to get everything ready, but from this campus, reminders for why we are doing this are never far away.