High on a mountain glacier, sheltering from a thunderstorm. With hail and wind buffeting the blue plastic tarp I’m clutching on to, and lightning cracking above, I realise that the boxes I’m sitting on contain several large high capacity batteries. My science teachers would be proud.

Four months earlier, I had returned to Vancouver from Svalbard, and an arctic winter that I will never forget. Touching down in YVR airport though, my mind was already on the list of ideas and tasks that would need to be tackled before fieldwork in July. My field campaign on Nordic Glacier last summer (see Notes from Nordic and Return to the Field) had been successful, but this season would present a whole host of new challenges. New glacier, new sensors, new objectives.

The overall goal of my project remains the same; to measure the weather conditions over a glacier surface, and to better understand how these conditions affect melt rates. One of the main differences for this year was that two stations would be installed on the glacier rather than one. The idea behind this is to see how weather and energy patterns vary across different points on the surface of the glacier, and how this in turn affects melting. This would mean a doubling of the number of sensors that would need to be prepared and tested.

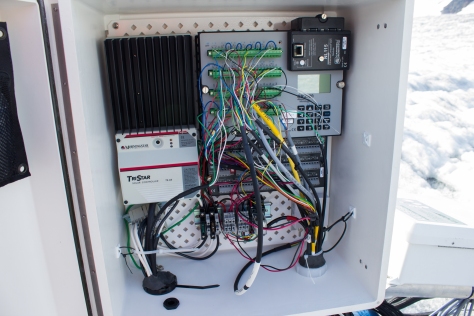

One of the more challenging aspects of last year’s campaign was ensuring the station remained powered throughout the summer. The nature of mountain weather means that persistent cloud can prevent a solar power system from providing enough energy to the sensors. In addition to doubling the number of stations this year, each station was fitted with a new, power hungry system for measuring turbulent air flow (an important mechanism for transferring heat between the atmosphere and glacier). The upshot is that a total of 12 large boat batteries and 4 solar panels are required this time in the hope of keeping everything beeping and recording over the season.

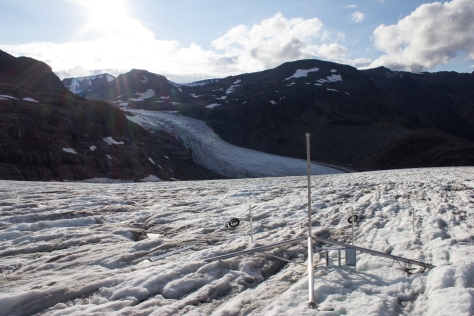

This year’s destination is Conrad Glacier, in the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia. I had visited Conrad at the end of last season to scout it out as a potential research site. Aside from its scientific merits, it is a beautiful part of the world; flanked by snow covered peaks, with forested valleys below and miles without engines. Named after Conrad Kain, a pioneering Austrian mountaineer who unlocked several first ascents in this area, the glacier is one of many in this region at risk of total disappearance. A recent study has forecast a 70% loss of BC’s glaciers this century, with almost total deglaciation in this region. Apart from global consequences to sea level rise, the loss of a glacier is the loss of a large water reservoir, putting pressure on ecosystems and communities (who use the water for drinking, irrigation, and hydro-power) during dry periods like we’ve had here this summer.

Being just a short journey south from last year’s glacier (Nordic), we would again base ourselves in the town of Golden prior to our flight into the mountains. After spending a day on the always spectacular drive from Vancouver to Golden, Valentina and I met up with Ben, a glaciologist from the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC) who would be joining us. Over some excellent burgers, we also had the chance to catch up with Tannis and Steve, friends of ours who run a ski lodge in the area, and have been consistently helpful. The plan for the next day was to drive to a staging area in the foothills to the south of Golden, and get all our gear into the mountains in as few chopper loads as possible (with thanks as always to Steve for his expertise on this).

Three helicopter flights (and some delays) later, all crew and equipment were accounted for on Conrad. Our campsite was just off the ice itself, on a rocky outcrop overlooking the glacier. The first evening was a battle against the weather to get tents set up in between heavy showers and gusty winds. Dinner was a simple affair, with everyone retiring to their sleeping bags early; sleep coming to the sound of fluttering tent fabric.

After breakfast the next morning, we set about finding the best route from camp on to the glacier; navigating the broken and crevassed ice along the glacier margin. Two locations had been selected for station 1 and 2 not far from camp. Each station would take about two days to install, with some additional time to prepare and secure everything for a season in the mountains.

The weather had a constant presence throughout the week, with wind, thunder and snow storms slowing the work somewhat, and making cooking a frigid task at the end of the day. Despite what felt like a cold spell to us, it was clear as soon as we saw the glacier that it was experiencing a warm season. In combination with low snowfall during the winter, warm temperatures had resulted in significant melt across the surface by the time we had arrived. Although close to what would normally be the beginning of the melt season, this year’s snow had already completely melted up to the high regions of the glacier.

With the stations coming together, Ben and I ventured higher up the glacier, and spent an afternoon installing ablation stakes. These stakes, installed along the length of the glacier, provided a record of how many meters of ice are lost or gained at the surface each year, and give an indication of the health or mass balance of the glacier (see Svalbard Part 2: Balancing Act). During the week on Conrad, Ben was also involved in carrying out a kinematic survey; using detailed GPS measurements to create a map of the glacier.

Due to weather delays, the final tasks for installing the stations were completed in the last few hours of the trip. With the helicopter due to pick us up that afternoon, I got moving early on the last day, and headed on to the ice before dawn to shore up the last few pieces of equipment from the elements, and to make sure all the systems were behaving. In the end, two full weather stations were installed, along with a time lapse camera to monitor conditions over the season.

It remains to be seen how the the glacier will respond to this year’s melt season, and on a personal level, how all the equipment will perform. A good or bad field campaign will have a major impact on the timeline for my studies and on the goals I hope to achieve. As our chopper lifted off from our disassembled camp and sped down the valley, I took one last glimpse at the stations and the glacier itself, before my eyes turned to home and my mind to the plan for the next trip.

A Note of Thanks: Just prior to leaving for field work, I received word that I was being awarded the Chih-Chuang and Yien-Ying Wang Hsieh Memorial Scholarship for research in Atmospheric Science. A sincere thank you to the Hsieh family. I was honoured to received it.

UP NEXT: The return to Conrad, and what we found.

A great read as always! Congrats on the award. Looking forward to seeing the timelapse changes on the glacier

Thanks for reading, Ronan; appreciate it! I’m just back from the return visit, so I should have the timelapse video up soon.

Hi Noel,

Really enjoyed the narrative and photos about the amazing trip to the glaciers. The quest for knowledge can call for a lot of hard work and initiative ! The line from the song comes to mind “Nobody said it was easy” ! Well done ! The folks in Sligo.

Many thanks! Glad you enjoyed the read. Not always easy, but always a privilege to be able to work in these amazing places.

A very engaging blog once again Noel, thanks for giving us such a descriptive insight into the project. Hope all went fairly well on the return.

Thanks again for reading, John. I’ll have an update on the return journey soon!

Only read this one now. Class. A friend of mine from work is checking out the updates too. Well done.